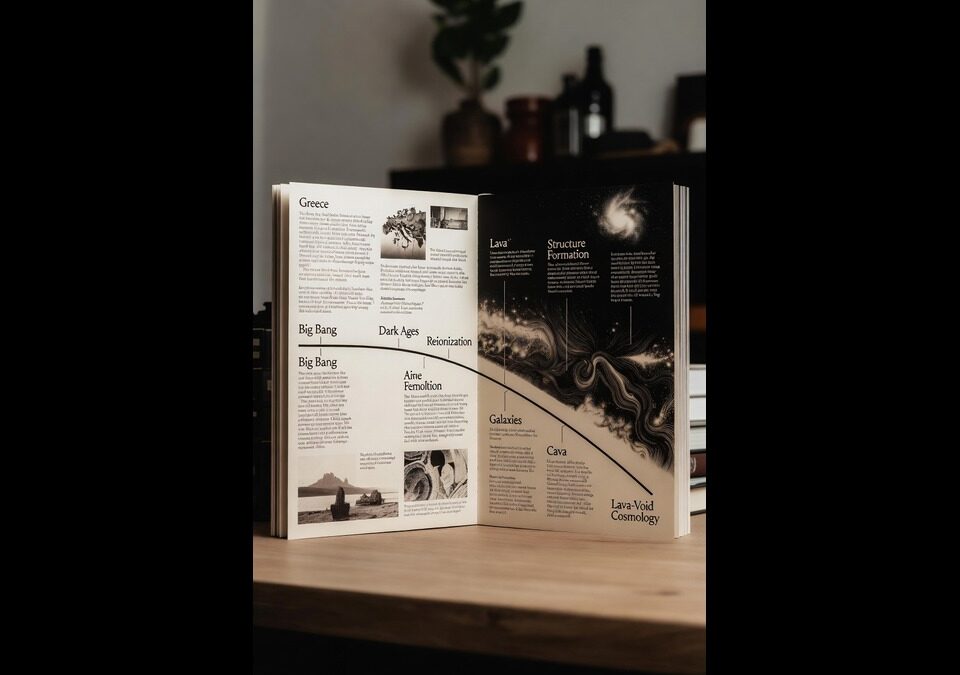

LVC: Comparative Synthesis of Sci-Fi Works of Art

February 2, 2026

Grok 4.1 Modes Explained: Stop Using Auto Mode (Fast vs Expert vs Thinking vs Heavy)

February 3, 2026 Music as Cultural Entropy Protocol: A Lava–Void Cosmology Extension

Music as Cultural Entropy Protocol: A Lava–Void Cosmology Extension

By C. Rich

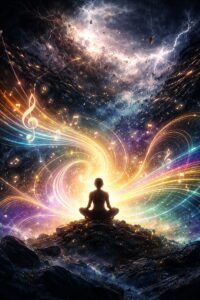

Music may feel emotional, personal, or even mysterious, but at its core, it is one of the oldest tools humans ever built for managing chaos. Long before we understood physics, entropy, or neuroscience, we discovered that sound organized in certain ways could calm us, excite us, bind groups together, and make meaning endure across time. In simple terms, music is how human beings learned to carve order out of noise.

Imagine the world as a constant flood of sensations, sounds, sights, emotions, and thoughts all competing for attention. Left alone, this flood becomes overwhelming. Music works because it creates patterns the mind can follow. A melody gives your attention a path. A rhythm gives time a shape. Harmony tells your brain what belongs together and what does not. When music is working well, it doesn’t eliminate chaos; it channels it, just enough to feel alive without feeling lost.

This is why music appears everywhere humans appear. The earliest known written song, carved into clay more than three thousand years ago, was not entertainment in the modern sense. It was a way to freeze sound in time so that future people could step into the same emotional and mental space as those who came before them. When someone plays that ancient melody today, the past briefly becomes present again. That is not magic. It is pattern preservation.

Over time, people discovered that certain sounds “fit” better than others. Simple ratios between notes, like the octave or the fifth, felt stable and pleasing because they reduced mental friction. The brain could predict what came next without strain. But humans also discovered something else: perfect order is impossible. No matter how carefully music is tuned, small mismatches always remain. Instead of ruining music, those imperfections give it motion. Tension pulls us forward. Resolution lets us breathe. Music lives in that balance.

As societies grew more complex, so did their music. Single melodies turned into multiple voices moving together. Later, composers learned how to travel freely between musical keys, accepting small compromises everywhere so that nothing became a dead end. In everyday terms, music learned how to explore without getting stuck. This mirrors how people themselves learn to navigate complex lives—trading perfection for flexibility.

Eventually, music pushed toward the edge. Romantic composers stretched emotional intensity to its limits. Jazz musicians embraced unpredictability and play. Modern styles sometimes abandon familiar structures entirely, forcing listeners to sit with uncertainty. None of this was random. Each step reflected how much disorder people could tolerate at a given time while still finding meaning.

Today, music lives inside machines. Streaming services hold nearly infinite libraries of sound, far more than any person could ever hear. Algorithms decide what flows toward us and what stays buried. Your playlists quietly shape your daily emotional landscape, whether you need focus, comfort, energy, or surprise. In this sense, music has become a feedback loop between human minds and intelligent systems, each influencing the other.

What remains constant across all of this is the human need for balance. Too much predictability and music becomes boring. Too much randomness and it becomes noise. Each person has a “just right” zone, where music feels engaging without being overwhelming. This balance can even be measured indirectly, through things like heart rate variability or how surprised the brain is by the next note.

Seen this way, music is not just art. It is evidence. It shows that humans, across history and technology, instinctively design ways to live between order and chaos. We do not want silence, and we do not want noise. We want flow. Music is one of the clearest, most universal proofs that meaning itself is something we actively shape, not something handed to us ready-made.

Ancient Period (c. 1400 BCE – c. 500 CE)

Music in early civilizations served ritual, ceremonial, and narrative functions. Following the Hurrian hymns, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, and other traditions employed instruments such as lyres, harps, flutes, and percussion. Notation remained rudimentary or mnemonic.

- In ancient Greece (c. 800–300 BCE), music integrated with poetry and drama; theorists like Pythagoras explored mathematical ratios in scales, influencing Western concepts of harmony and modes.

- The Roman Empire adopted and disseminated Greek practices, while early Christian chant emerged by the late period.

Surviving examples include the Delphic Hymns and Seikilos epitaph (c. 100–200 CE), the next oldest notated pieces after the Hurrian material.

Medieval Period (c. 500–1400 CE)

Music became closely tied to the Christian Church in Europe. Gregorian chant, monophonic, modal, and unaccompanied, dominated sacred repertoire. Notation evolved significantly with neumes (c. 9th century) and Guido d’Arezzo’s staff system (c. 1000 CE), enabling more precise transmission.

Secular traditions included troubadours and trouvères in France, and Minnesang in Germany, featuring monophonic songs with lute or vielle accompaniment. By the late medieval era, polyphony developed (e.g., organum by Léonin and Pérotin), introducing multiple independent voices.

Renaissance Period (c. 1400–1600 CE)

A “rebirth” emphasized humanism, clarity, and balance. Polyphonic sacred music flourished with composers such as Josquin des Prez and Palestrina, using imitative counterpoint and modal scales. Secular forms included the madrigal (expressive part-songs) and chansons. Printing (Gutenberg, c. 1450) accelerated dissemination of music scores.

Instrumental music gained prominence, with lutes, viols, and early keyboards.

Baroque Period (c. 1600–1750 CE)

The era introduced tonality, basso continuo, and dramatic expression. Opera emerged (Monteverdi, c. 1607), alongside oratorio and concerto grosso. Key figures include J.S. Bach (complex counterpoint), Handel (oratorios), and Vivaldi (concertos). Instruments standardized further, with the violin family maturing.

Classical Period (c. 1750–1820 CE)

Emphasis shifted to clarity, balance, and form. Sonata form, symphonies, string quartets, and piano sonatas dominated. Major composers: Haydn (symphonic pioneer), Mozart (prolific mastery across genres), and Beethoven (bridging to Romanticism with expanded emotional range and structural innovation).

Romantic Period (c. 1820–1900 CE)

Music became more expressive, programmatic, and individualistic, reflecting nationalism and personal emotion. Larger orchestras, chromatic harmony, and extended forms prevailed. Composers include Schubert (lieder), Chopin (piano works), Wagner (music drama and leitmotifs), Brahms (absolute music), and Tchaikovsky (orchestral color).

20th and 21st Centuries (c. 1900–present)

Diversity exploded with modernism, atonality, serialism (Schoenberg), impressionism (Debussy), neoclassicism (Stravinsky), minimalism (Reich, Glass), and electronic/experimental music. Jazz emerged in the early 1900s (blues roots, improvisation), influencing global styles. Popular music genres, blues, rock ‘n’ roll (1950s), pop, hip-hop (1970s–80s), electronic dance music, and streaming-era fusions, arose alongside technological advances (recording, radio, digital production).

Today, music encompasses global cross-pollination, AI-assisted composition, immersive audio, and platforms enabling instant worldwide access, while preserving ancient roots in folk and ritual traditions.

This trajectory, from a single preserved hymn in cuneiform to the vast, interconnected ecosystem of contemporary music, illustrates humanity’s enduring impulse to organize sound for expression, ritual, and innovation.

In the end, music teaches a simple lesson in human terms: survival is not about eliminating disorder, but learning how to dance with it. Music helps humans create order from chaos, shaping meaning across history and technology. Music as a Human Tool for Order in a Chaotic World. Read the PDF (1st link below) about the science of it.

Music_as_Cultural_Entropy_Protocol_LVC

Music: Analog Angst to Artificial Intelligence

C. Rich