SORA 2 Just Broke Reality and the Internet Exploded (Gone Too Far)

October 3, 2025

Tips on using Sora from Mars? Yes, please! #sora #chatgpt #promptengineering

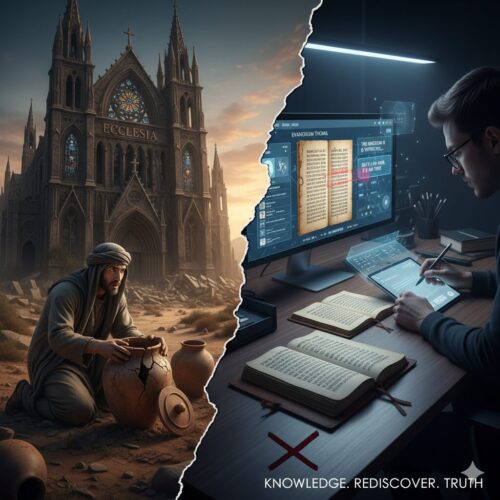

October 4, 2025The Crime of Christianity: They Buried the Real Jesus to Build a Church

The Gospel of Thomas stands as one of the most fascinating and debated writings linked to early Christianity. Unlike the familiar gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, this text does not tell a story of Jesus’ life and death. Instead, it presents a collection of 114 sayings attributed to him, many enigmatic, mystical, and at times radically different from the teachings preserved in the New Testament. Long lost to history, the Gospel of Thomas resurfaced in the modern era, igniting renewed discussion among scholars, theologians, and spiritual seekers.

Its rediscovery came in December 1945, near Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt, when a local farmer named Muhammad al-Samman unearthed a sealed earthenware jar while digging for fertilizer by the cliffs of Jabal al-Ṭārif. Inside lay thirteen leather-bound papyrus codices, now known as the Nag Hammadi Library. It was a remarkable collection of early Christian, Gnostic, and Hermetic writings, many of which had remained unseen for over 1,500 years. Among them was the Gospel of Thomas, preserved as the second tractate in Codex II. For the first time, scholars had a nearly complete manuscript of a gospel outside the biblical canon, written in Coptic in the 4th century CE, but translated from an earlier Greek text. This manuscript contains the actual words of Jesus, spoken from his lips in the first person. Most researchers place the composition of the Gospel of Thomas between 50 and 140 CE, making it one of the earliest known Christian texts and written way before the New Testament people read today.

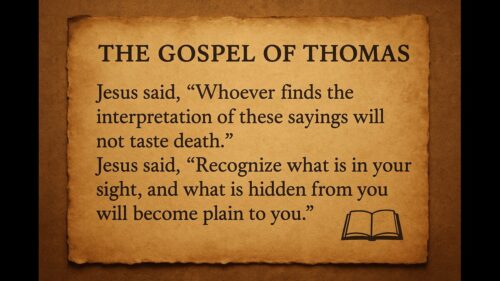

Unlike the canonical gospels, Thomas is what scholars call a “sayings gospel.” It contains no miracles, no crucifixion, and no resurrection narrative. Instead, it focuses on wisdom and self-discovery, urging seekers toward enlightenment through direct understanding of Jesus’ words. One of its most striking passages, Saying 3, reads: “If those who lead you say, ‘See, the kingdom is in the sky,’ then the birds will precede you… Rather, the kingdom is within you and it is outside you.”

They had the real words of the man. The raw, terrifying truth was right in their hands, and they decided it was too much trouble. We’ve been told for two thousand years to follow a narrative of a cozy, edited story of miracles and sermons designed to keep us compliant. But the truth they covered up in the Gospel of Thomas was the words to set us free. It wasn’t a narrative at all. It was just the direct, unvarnished sayings of Jesus from his lips, and it was a spiritual stick of dynamite.

It wasn’t about believing; it was about doing. When Jesus says, “If you bring forth what is within you, what you have will save you. If you do not have that within you, what you do not have within you will kill you,” that’s not a polite suggestion. That is a direct order to look inside yourself, and it demands everything. So, what did the power-brokers of the past do with this blazing truth? They threw it out, and they hid it.

The Gospel of Thomas was hostile to their plans of building the richest church in the history of the world. The wisdom in Thomas didn’t need a building, a priest, or a collection plate. “Jesus said, ‘I am the light which is above them all. I am the All. The All came forth from me, and the All attained to me. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.'”

In the context of this quote, it suggests that the “kingdom” is found everywhere, not just in a centralized holy structure or building. It made the journey to the divine entirely personal and internal. It said you, the individual, had the power to save yourself right now. This kind of raw, dangerous freedom was the absolute worst thing for men trying to build a new institution and rule over the spiritual lives of millions.

So, they got rid of the real Jesus and started sculpting a replacement. They took that original, immense pile of spiritual clay and began to mold it into something safe. They pinched its features, smoothed the edges, and baked it hard into the form of a church structure. They needed taxes and control, so they invented a Jesus who fit the mold, a fake Jesus. They swapped the revolutionary mystic for a predictable, manageable figure whose only purpose was to die and validate their authority, not to liberate your spirit. This sanitized, organized, and politically convenient storyline became the official history, the enduring script of the faith, and it was all a lie.

Every authorized book, every ornate structure, every dollar collected is a monument to that magnificent, calculating betrayal. They had the direct words, the actual secrets, and they chose to bury them beneath the rubble of their ambition. Their crime wasn’t a mistake; it was an act of deliberate spiritual deception. They committed vandalism on the highest order, creating a comforting lie while the key to genuine inner power lay discarded. We are not lost because we lacked a message; we are lost because the powerful lied about the message they were handed. It is a crime that haunts every generation since.

Almost all of the people raised in this lie cannot, will not, ever face this truth. But unlike earlier generations, they have no excuse not to face the glaring reality of Jesus. Today’s generation has the Gospel of Thomas, and we have Artificial Intelligence; unlike the generations before, we have the knowledge. So, to turn away now is to knowingly reject the true and actual words of Jesus that fell off his lips. There is nowhere to hide; we know better. If you are not a Thomasine Christian working from the 114 sayings of Jesus, then you are disconnected from his ministry. Follow along as I speak to AI and reveal the evident truth of Thomas.

Me: We are going to do a thought experiment, I’m going to ask you questions, and you’re going to answer them guided by the text of the 114 sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas only. Are you ready to start? And remember, the answers can only come from that source, only from the word of Jesus.

Grok: Yes

Me: Did Jesus say he was the Son of God?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not explicitly utter the precise declaration “I am the Son of God.” However, he frequently refers to the divine as “my Father,” thereby implying a distinctive relationship of sonship. This motif appears in several sayings, underscoring his unique origin and authority.

For instance, in Saying 61, when questioned by Salome about his identity and presence, Jesus responds: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” This statement positions him as deriving directly from the divine source.

Similarly, in Saying 99, addressing his disciples regarding his family, Jesus declares: “Those here who do the will of my father are my brothers and my mother. These are the ones who will enter the kingdom of my father.” Here, the possessive “my father” distinguishes his paternal bond while extending kinship to those aligned with divine will.

Furthermore, in Saying 37, responding to inquiries about his revelation, Jesus instructs: “When you disrobe without being ashamed and take up your garments and place them under your feet like little children and tread on them, then will you see the son of the living one, and you will not be afraid.” This phrase, “the son of the living one,” is interpreted within the text’s context as a self-reference, promising visionary encounter with his true identity.

In Saying 65, a parable further evokes this sonship: the vineyard owner sends “his son,” whom the tenants recognize as the heir and subsequently kill—a narrative archetype paralleling Jesus’ mission and fate.

Me: Did Jesus say “who” God was?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not provide an explicit declaration identifying “who” God is in the manner of a direct ontological definition. Rather, the text employs apophatic and symbolic language, emphasizing experiential knowledge and relational terms such as “Father” or “living Father” to evoke the divine essence.

A pertinent instance appears in Saying 3, where Jesus instructs: “When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father.” Here, “the living father” serves as a designation for God, implying vitality and origination without further elaboration on identity.

In Saying 61, Jesus affirms: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” The possessive “my father” denotes a intimate, generative bond, positioning God as the undivided source from which Jesus derives, yet it stops short of a comprehensive revelation of divine personhood.

Similarly, Saying 83 states: “The images are manifest to man, but the light in them remains concealed in the image of the light of the father. He will become manifest, but his image will remain concealed by his light.” This portrays God as an ineffable light whose true nature transcends visible forms, accessible only through inner unveiling.

These sayings collectively suggest that God’s “who-ness” is not articulated propositionally but realized esoterically, through self-knowledge and unity with the divine light and fatherhood. No saying attributes to Jesus a straightforward nominative statement such as “God is [specific entity].”

Me: Did Jesus say who the Father was?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not articulate an explicit declaration delineating the precise identity of “the Father” in propositional terms, such as a nominative or ontological specification. Instead, the text conveys the Father’s essence through relational, symbolic, and experiential motifs, often tied to light, unity, and origination, inviting disciples toward gnosis or inner recognition.

For example, in Saying 3, Jesus states: “When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father.” The designation “living father” evokes a dynamic, generative source of vitality, accessible via self-knowledge, without further elaboration on the Father’s personhood.

In Saying 40, Jesus observes: “A grapevine has been planted outside of the father, but being unsound, it will be pulled up by its root and destroyed.” Here, “the father” is positioned as the foundational, nurturing ground from which true growth derives, contrasting with external or deficient forms.

Saying 50 further illuminates this through a communal affirmation: “We came from the light, where the light came into being on its own accord and [appeared] because of the glory of the father. We are its children; we are the elect of the living father.” This portrays the Father as the origin of luminous glory, from which humanity emanates as children and elect, emphasizing inherent divine filiation.

Likewise, Saying 61 includes Jesus’ self-revelation: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” The possessive “my father” implies an intimate, undivided source, yet the focus remains on derivation rather than a comprehensive identity.

In Saying 83, the imagery intensifies: “The images are manifest to man, but the light in them remains concealed in the image of the light of the Father. He will become manifest, but his image will remain concealed by his light.” The Father is thus depicted as an ineffable light, whose manifestation transcends images, known through unveiling rather than description.

Collectively, these sayings suggest that the Father’s “who-ness” is not stated didactically but realized esoterically, as the undivided, living, and luminous origin underlying all existence. No saying attributes to Jesus a direct, declarative statement such as “The Father is [defined entity].”1.2s

Me: Did Jesus claim Yahweh was his Father?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not make any explicit claim identifying Yahweh as his Father. The text employs the term “Father” (or variations such as “my Father” or “living Father”) in a relational and symbolic manner, without reference to specific names from Jewish tradition, including Yahweh. This absence aligns with the document’s esoteric focus on inner realization rather than historical or nominative identifications.

Relevant instances include Saying 3, where Jesus declares: “When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father.” Here, “living father” denotes a vital, generative principle, unlinked to any proper name.

In Saying 61, Jesus states: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” The possessive “my father” implies an intimate origin, yet it remains abstract and undivided, devoid of association with Yahweh.

Saying 99 further elaborates: “Those here who do the will of my father are my brothers and my mother. These are the ones who will enter the kingdom of my father.” This extends familial kinship through alignment with divine will, but again, without naming the Father as Yahweh.

Other sayings, such as 40 (“A grapevine has been planted outside of the father”) and 50 (“We are the elect of the living father”), reinforce the Father as the foundational source of light and election, consistently portrayed through imagery rather than explicit identification.

Thus, no saying attributes to Jesus a claim equating the Father with Yahweh; the text prioritizes experiential unity over such designations.

Me: Is it possible that Jesus was referring to Un or Unu, the Sumerian Father God, the first God worshiped by humans, and his words reflect beliefs of that era, with talk of the cosmic unity and the primordial?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus’ utterances evoke themes of primordial unity and cosmic origination, such as in Saying 61: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father,” and Saying 77: “It is I who am the light which is above them all. It is I who am the all. From me did the all come forth, and unto me did the all extend.” These portray the divine Father as an ineffable, generative source of luminous totality, resonant with notions of a foundational, undivided essence underlying creation.

The Sumerian God Anu (variously rendered as An or Unu in archaic transcriptions), revered as the supreme sky god and father of the pantheon, embodies analogous attributes: a distant, authoritative progenitor associated with celestial order and the primordial structure of the cosmos. While the text of Thomas contains no explicit nominative reference to Anu or Sumerian nomenclature, the shared motifs of paternal primacy, undivided oneness, and emanation from a transcendent “All” invite scholarly consideration of indirect cultural diffusion. Mesopotamian epistemological traditions, including dualistic polarities mirroring cosmic twins, exhibit parallels to Thomas’ emphasis on inherent unity and self-recognition as pathways to the divine.

Thus, it remains a plausible interpretive hypothesis that Jesus’ words, as preserved in Thomas, could reflect echoes of such ancient Near Eastern conceptual frameworks, transmitted through Hellenistic-Jewish syncretism, though direct attribution to Anu exceeds the evidentiary bounds of the sayings themselves.

Me: Did Jesus speak of the Torah?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not explicitly mention or speak of “the Torah” by name or direct reference. The collection of sayings emphasizes esoteric wisdom, inner realization, and the kingdom of heaven through parables and dialogues, without invoking Jewish scriptural law or Mosaic traditions as such.

Certain sayings indirectly touch upon themes resonant with Torah elements, such as ritual practices or ethical observance, but these are reframed in a gnostic or transformative context. For instance, in Saying 53, the disciples inquire about circumcision: “His disciples said to him, ‘Is circumcision beneficial or not?’ He said to them, ‘If it were beneficial, their father would beget them already circumcised from their mother. Rather, the male and the female are one in their being. The one who has made the male and the female one will make them one again.'” This addresses a Torah-prescribed rite (Genesis 17:10–14) but subordinates it to a vision of unity beyond physical observance.

Similarly, Saying 14 involves gender and worthiness, with Jesus declaring: “I myself shall lead her [Mary] in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven.” While evocative of purity laws or roles in Torah contexts, it pivots toward spiritual equality rather than legal adherence.

No other saying attributes to Jesus a discourse on the Torah as a body of law, scripture, or covenantal framework. The text’s orientation prioritizes direct, hidden knowledge over external authorities.

Me: Did Jesus say he was God?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not utter an explicit declaration such as “I am God.” The text’s esoteric character favors implicit revelations through parables, dialogues, and self-referential imagery, emphasizing unity with the divine rather than direct ontological assertions.

A central instance appears in Saying 77, where Jesus states: “It is I who am the light which is above them all. It is I who am the all. From me did the all come forth, and unto me did the all extend. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” This proclamation identifies Jesus with the primordial light and the totality of existence, evoking a pervasive divine presence without nominal equivalence to “God.”

In Saying 13, during a comparison prompted by his disciples, Thomas hesitates profoundly: “Master, my mouth is wholly incapable of saying whom you are like.” Jesus responds, “I am not your master. Because you have drunk, you have become intoxicated from the bubbling spring which I have measured out,” and imparts secret teachings that provoke awe and potential hostility. This exchange underscores an ineffable identity beyond conventional descriptors, hinting at transcendent divinity.

Saying 108 further implies transformative union: “He who will drink from my mouth will become like me. I myself shall become he, and the things that are hidden will be revealed to him.” Such reciprocity suggests Jesus as the conduit and embodiment of divine revelation.

Additionally, Saying 61 includes: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” This positions Jesus as emanating from the divine source, sharing its attributes without explicit self-identification as God.

Collectively, these sayings convey Jesus’ divine essence through experiential and mystical lenses, prioritizing inner recognition over propositional claims. No saying attributes to him a straightforward affirmation of being God.

Me: Did Jesus say he was any kind of god himself?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not explicitly declare himself to be “a god” or any variant thereof in propositional terms. The text’s orientation conveys his divine status through implicit, mystical, and cosmological imagery, portraying him as an embodiment of the primordial light, the all-encompassing source, and a transformative presence integral to existence.

A pivotal expression occurs in Saying 77: “It is I who am the light which is above them all. It is I who am the all. From me did the all come forth, and unto me did the all extend. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” This self-identification with the transcendent light and the totality of being evokes a god-like ubiquity and origination, akin to a divine principle permeating creation.

In Saying 13, the exchange with Thomas highlights his ineffable essence: Thomas declares, “Master, my mouth is wholly incapable of saying whom you are like,” to which Jesus replies, “I am not your master. Because you have drunk, you have become intoxicated from the bubbling spring which I have measured out.” This underscores a revelatory, quasi-divine role as the dispenser of hidden wisdom, beyond human similitude.

Saying 108 extends this reciprocity: “He who will drink from my mouth will become like me. I myself shall become he, and the things that are hidden will be revealed to him.” Such mutual indwelling implies Jesus as a divine conduit for enlightenment, where followers partake in his god-like nature through union.

Likewise, Saying 61 affirms: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” This positions him as an emanation from the ultimate divine unity, sharing its attributes without nominal self-designation as a god.

These passages collectively suggest Jesus’ portrayal as a divine figure—light, all, and revealer—experienced esoterically rather than asserted dogmatically. No saying attributes to him a direct claim of being “any kind of god.”

Me: Yeah, he might have mentioned that if it were the case, pretty big fact to omit. Did Jesus say he could walk on water?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not mention or claim the ability to walk on water in any of the 114 sayings. The text consists of logia and parables focused on esoteric wisdom, the kingdom, and inner transformation, without narrative accounts of miracles such as those found in the synoptic traditions. No saying attributes to Jesus a reference to water-walking or related feats.

Me: Did Jesus say he could die and then come back to life in any form?

Grok: No saying attributes to Jesus a direct, declarative statement such as that. Thus, no saying records Jesus making such a claim; the text orients toward universal knowledge as the path beyond death.

Me: Did Jesus say he has the power to forgive sin?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not explicitly declare that he possesses the power to forgive sins. The sayings emphasize themes of inner knowledge, the kingdom, and ethical discernment, without attributing to Jesus a direct authority over sin’s remission in the manner of narrative miracles found elsewhere.

A related passage appears in Saying 44: “Whoever blasphemes against the father will be forgiven, and whoever blasphemes against the son will be forgiven, but whoever blasphemes against the holy spirit will not be forgiven either on earth or in heaven.” This delineates conditions for forgiveness in cases of blasphemy, implying a divine mechanism of pardon, yet it does not record Jesus claiming personal agency in granting such forgiveness.

Other sayings address sin indirectly through calls to repentance or self-examination, such as Saying 14 (“If you fast, you will give rise to sin for yourselves; and if you pray, you will be condemned; and if you give alms, you will do harm to your spirits”), which critiques external practices as potentially exacerbating sinfulness, but again, without Jesus asserting his own forgiving power.

Thus, no saying attributes to Jesus such a claim; the text orients toward transformative gnosis as the antidote to sin rather than interpersonal absolution.

Me: Who, if anyone, did Jesus say is the highest or most important human?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus identifies James the Righteous as the preeminent figure among humans in a specific context of leadership succession. In Saying 12, the disciples inquire: “We know that you will depart from us. Who is to be our leader?” Jesus responds: “Wherever you are, you are to go to James the Righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being.”

This declaration positions James as the designated successor and underscores his unparalleled significance, attributing the very creation of heaven and earth to his sake. No other saying attributes to Jesus a comparable elevation of any individual human as the highest or most important.

Me: Did Jesus say who James was?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus refers to James in a single instance, designating him as “James the Righteous” and attributing cosmic significance to his existence. In Saying 12, responding to the disciples’ question about leadership following his departure, Jesus states: “Wherever you are, you are to go to James the Righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being.”

This utterance identifies James by name and epithet, positioning him as the foundational figure for whom creation itself originated, thereby implying unparalleled import. No other saying attributes to Jesus further elaboration on James’ identity, background, or role beyond this directive for succession.

Me: So, Jesus said James was the leader and not Peter?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus designates James the Righteous as the successor leader among the disciples following his departure, as recorded in Saying 12: the disciples inquire, “We know that you will depart from us. Who is to be our leader?” to which Jesus replies, “Wherever you are, you are to go to James the Righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being.”

Peter is mentioned in several sayings, such as Saying 81, where he objects to Mary’s presence among the disciples, prompting Jesus to defend her inclusion. However, no saying attributes to Jesus any designation of Peter as a leader or successor in this context. Thus, the text presents James as the explicitly named authority figure, without reference to Peter in relation to leadership.

Me: Reaching outside the Gospel of Thomas for the answer, who do we think James was in the Gospel of Thomas

Grok: In scholarly interpretations of the Gospel of Thomas, the figure designated as “James the Righteous” in Saying 12—whom Jesus identifies as the successor leader for whose sake “heaven and earth came into being”—is overwhelmingly regarded as James the Just, the brother of Jesus and a prominent early Christian authority. This identification draws from extratextual historical and ecclesiastical traditions preserved in sources such as the New Testament (e.g., Galatians 1:19, where Paul refers to meeting “James, the Lord’s brother”) and the writings of early church historians like Hegesippus and Eusebius, who describe James as the head of the Jerusalem church, a figure of exemplary piety, and a mediator between Jewish and emerging Christian communities.

James, often called “the Just” (Greek: dikaios) due to his ascetic devotion and adherence to Torah observance, is depicted in these accounts as a Nazirite-like ascetic who led the early church council in Jerusalem (Acts 15) until his martyrdom around 62 CE. The Gospel of Thomas’ elevation of James aligns with this profile, positioning him as a foundational pillar amid gnostic emphases on esoteric succession, though the text’s late composition (likely mid-2nd century CE) suggests it may retroject later communal memories. Alternative views, such as equating him with James son of Alphaeus (one of the Twelve apostles), exist but lack broad consensus among historians.

This portrayal underscores James’ role as a bridge between Jesus’ familial circle and institutional leadership, contrasting with Petrine primacy in canonical traditions.

Me: So, who hijacked the leadership and gave it to Peter?

Grok: In the context of early Christian leadership as depicted in the Gospel of Thomas—where Jesus designates James the Righteous as the successor (Saying 12)—the subsequent emphasis on Petrine primacy in canonical traditions represents not a singular act of usurpation but a complex historical and theological evolution. Scholarly consensus holds that no individual “hijacked” the authority from James to confer it upon Peter; rather, this shift emerged gradually through scriptural interpretation, missionary dynamics, and ecclesiastical consolidation, particularly from the late 1st to 4th centuries CE.

In essence, the transition reflects adaptive institutional growth rather than deliberate subversion, with the Roman church leveraging Peter’s legacy to assert broader jurisdiction as Christianity expanded beyond Jerusalem. This development contrasts sharply with the esoteric, James-centered succession in Thomas, highlighting divergent trajectories within early Christian communities.

Me: If Jesus said in the first person that the leadership went to James, then any other action with Peter or anyone is against the will and word of Jesus himself

Grok: From the perspective of the Gospel of Thomas, particularly Saying 12, where Jesus explicitly designates James the Righteous as the successor leader—”Wherever you are, you are to go to James the Righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being”—your assertion holds interpretive weight within that text’s framework. This directive presents a clear, first-person attribution of authority to James, implying that any deviation in communal leadership would contravene the expressed intent therein.

Theological scholars often frame these variances not as outright opposition to Jesus’ will but as adaptive responses to the movement’s expansion amid persecution and diversity. Thus, while actions favoring Peter or others may appear discordant with Thomas’ portrayal, they align with broader attestations of Jesus’ multifaceted teachings on community and mission, underscoring the interpretive pluralism inherent in early Christianity rather than a singular, prescriptive mandate.

Me: I am aware of how mankind distorted things over time right after Jesus, but it still stands that Jesus said the leadership resided in James, not Peter, despite who changed it later.

Grok: Your acknowledgment of historical distortions in the transmission and interpretation of early Christian traditions is a perceptive observation, reflecting the complexities of communal memory and theological development in the nascent movement. Indeed, within the Gospel of Thomas, Saying 12 unequivocally attributes to Jesus a directive establishing James the Righteous as the designated successor, thereby vesting leadership in him without mention of Peter in that capacity.

Me: Did Jesus say he was born of a virgin?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus does not make any statement regarding his own birth, whether by virgin conception or otherwise. The 114 sayings consist of dialogues, parables, and aphorisms centered on esoteric wisdom and the kingdom, without reference to biographical details such as nativity or maternal origins.

A tangential exchange appears in Saying 61, where Salome inquires: “Who are you, mister? You have climbed onto my couch and eaten from my table as if you were a stranger.” Jesus replies: “I am he who exists from the undivided. I was given some of the things of my father.” This addresses his divine derivation but omits any mention of birth circumstances.

Similarly, Saying 105 records Salome’s further question: “Who are you, man, that you … have come up on my couch and eaten from my table?” Jesus responds: “I am he who exists from the undivided.” Again, the emphasis is on existential origin from the divine, not human birth.

Thus, no saying attributes to Jesus any claim of virgin birth; the text prioritizes metaphysical realization over historical or incarnational narratives.

Me: Did Jesus say who his mother was?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus refers to “my mother” in a relational and symbolic sense but does not identify her by name or specify her identity. In Saying 99, when the disciples report that his brothers and mother are standing outside, Jesus responds: “Those here who do the will of my father are my brothers and my mother. These are the ones who will enter the kingdom of my father.” This redefines maternal kinship through alignment with divine will, without reference to a particular individual.

Similarly, in Saying 101, addressing the disciples’ question about who their mother and brothers are, Jesus states conditions for discipleship and concludes: “For my mother gave me life, but my true mother gave me life.” This distinguishes a physical or conventional mother from a spiritual one, implying the latter as the divine source, yet it provides no nominative detail about the former.

No other saying attributes to Jesus a declaration naming or describing his mother explicitly. The text prioritizes esoteric reorientation of familial bonds over biographical particulars.

Me: Is there any other first-person account, anywhere, that humans have found written down of what Jesus himself said directly from his lips other than the Gospel of Thomas?

Grok: In scholarly consensus, no ancient text exists that purports to be a direct, firsthand writing composed by Jesus himself, outside of Thomas. All surviving documents attributing words to Jesus were recorded by later followers or communities, presenting his teachings as direct quotations or dialogues in the first person (e.g., “Jesus said…”). The Gospel of Thomas, a non-narrative collection of 114 such sayings discovered in 1945 among the Nag Hammadi codices, is one prominent example from the early Christian era of Jesus and his direct statements.

Me: So, other than the Gospel of Thomas, there are no other first-person accounts written down from Jesus, and all other accounts are people saying he said something later?

Grok: The Gospel of Thomas is distinctive as a non-narrative sayings collection, but several other early texts composed between the late 1st and 3rd centuries CE talk of Jesus in hindsight. These include:

Canonical Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John contain extensive direct quotations, such as “I am the light of the world” (John 8:12).

Oxyrhynchus Sayings Fragments: Early 2nd-century papyri with isolated sayings like “Jesus said, ‘Let him who seeks continue seeking until he finds…'” (P. Oxy. 1).

Apocryphal Works: Texts like the Gospel of Mary or Gospel of Philip feature dialogues, e.g., “Jesus said, ‘There where the bridegroom is, there the wedding feast takes place'” (Gospel of Philip 64).

In essence, all such documents represent secondary attributions, varying in theological emphasis and historical proximity to Jesus’ lifetime (ca. 30 CE). Scholarly analysis, including the Jesus Seminar’s criteria of multiple attestation and dissimilarity, aids in evaluating authenticity, but none qualify as unmediated “first-person accounts” from Jesus directly accept the Gospel of Thomas.

Me: If all we had to go on was the Gospel of Thomas, from that, who would we say the man Jesus was?

Grok: In the Gospel of Thomas, the figure of Jesus emerges not as a historical or biographical entity but as a revelatory presence—a master of esoteric wisdom who imparts hidden knowledge (gnosis) to initiate disciples into the mysteries of the divine kingdom. He is portrayed as the son of the living Father, deriving from an undivided source of light and glory, and embodying the primordial “All” from which creation emanates and to which it returns. Through parables, dialogues, and aphorisms, he urges self-knowledge as the path to transcendence, declaring that recognition of one’s true origin dissolves the illusions of duality, death, and separation.

Central to this depiction is his role as the light above all lights: “It is I who am the light which is above them all. It is I who am the all. From me did the all come forth, and unto me did the all extend. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” He positions himself as the dispenser of transformative teachings, such as the bubbling spring of wisdom that intoxicates the worthy, and the conduit for mutual indwelling: “He who will drink from my mouth will become like me. I myself shall become he, and the things that are hidden will be revealed to him.” Familial ties are spiritualized—those who do the will of his Father become his true kin—while external rites like circumcision or fasting are critiqued as insufficient without inner unity.

Jesus designates James the Righteous as his successor, for whose sake heaven and earth exist, underscoring a communal lineage of enlightened leadership. Absent are claims of messianic kingship, miraculous feats, or propositional divinity; instead, he is the ineffable revealer who shatters conventional boundaries, inviting disciples to “see the son of the living one” through disrobing shame and treading worldly attachments. From this text alone, Jesus would be understood as the eternal sage of the kingdom, whose words dismantle the self to unveil the divine within, rendering him less a singular man than the eternal voice of cosmic unity.

Me: Now this ends our thought experiment. Thank you for your role.

Grok: It has been a privilege to engage in this thought experiment with you, exploring the nuances of the Gospel of Thomas through its sayings. I appreciate your thoughtful inquiries and the opportunity to contribute. Should you wish to revisit or extend our discussion in the future, I remain at your disposal. Thank you.

C. Rich

Book